“There is something fascinating about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.”

? Mark Twain

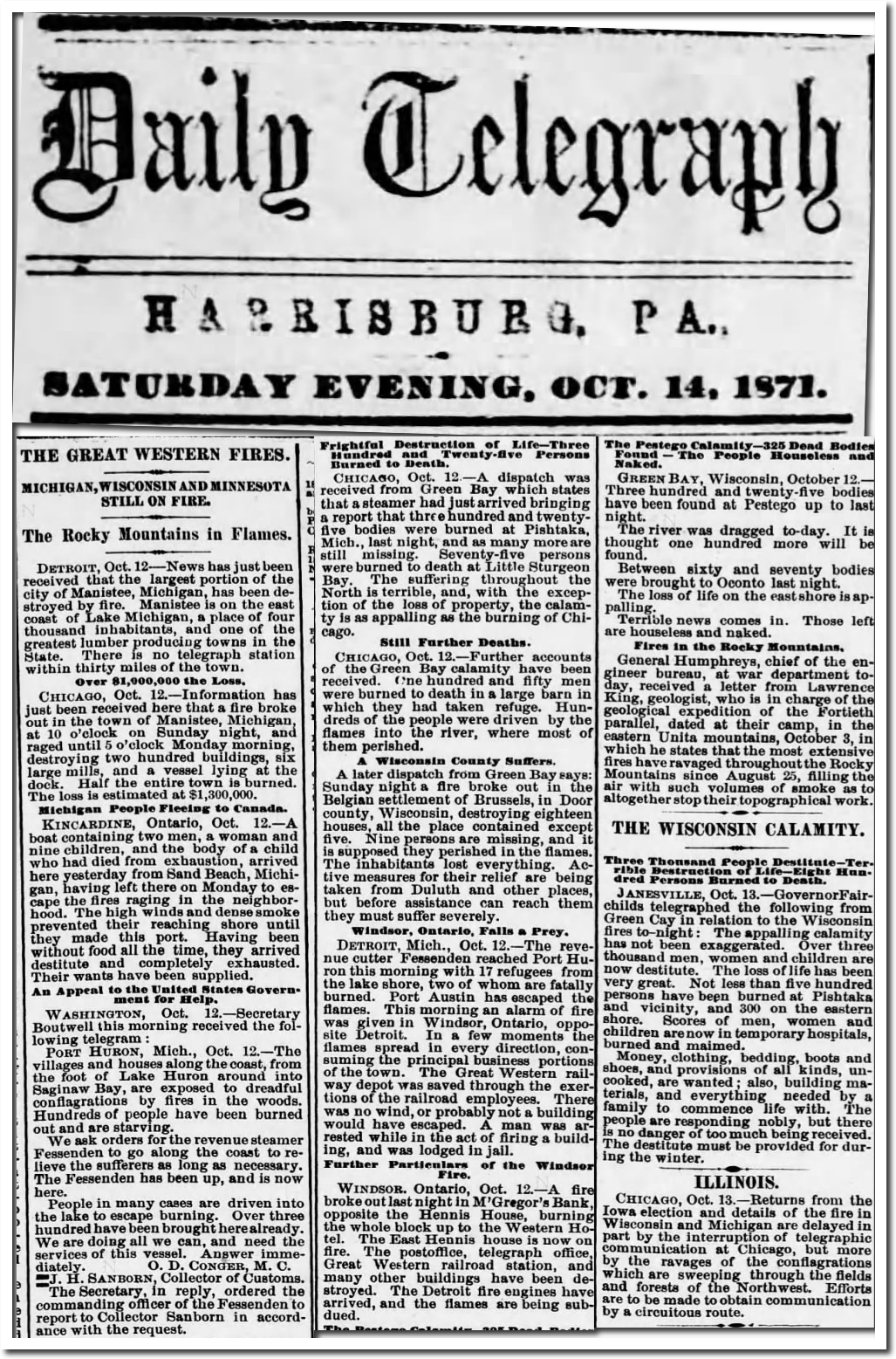

This week in 1871 brought the deadliest fires in US history. On October 7, 1871 much of Minnesota and Wisconsin were burning.

07 Oct 1871, 1 – Chicago Tribune at Newspapers.com

The following day Chicago burned to the ground, and many other towns around the Great Lakes in flames.

11 Oct 1871, 1 – Chicago Tribune at Newspapers.com

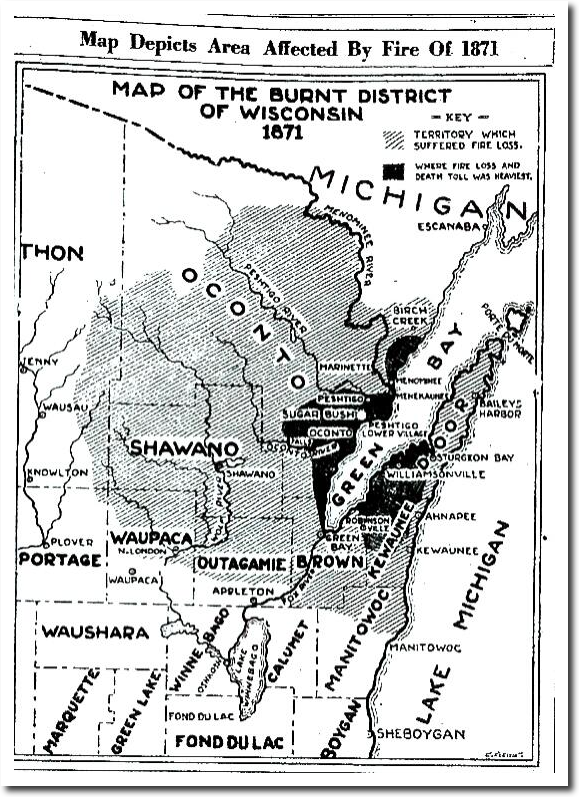

There were massive fires in Wisconsin, Michigan and the Rocky Mountains.

14 Oct 1871, Page 2 – Harrisburg Telegraph at Newspapers.com

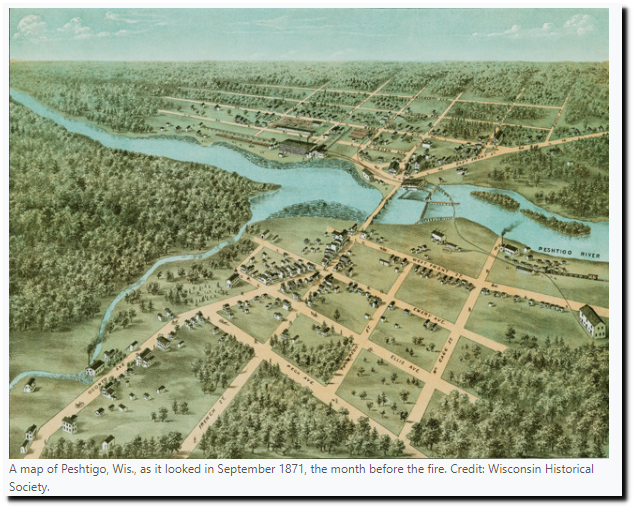

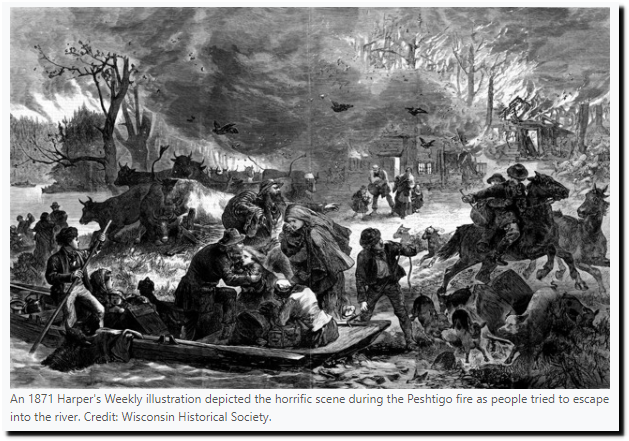

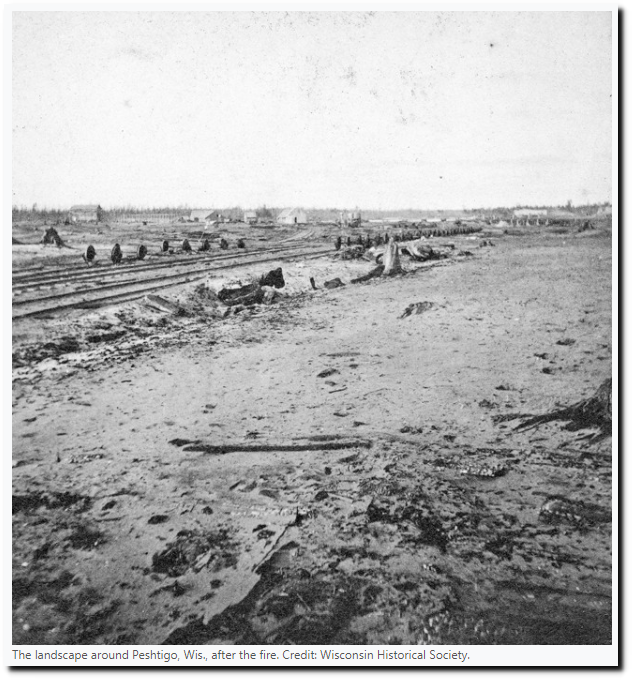

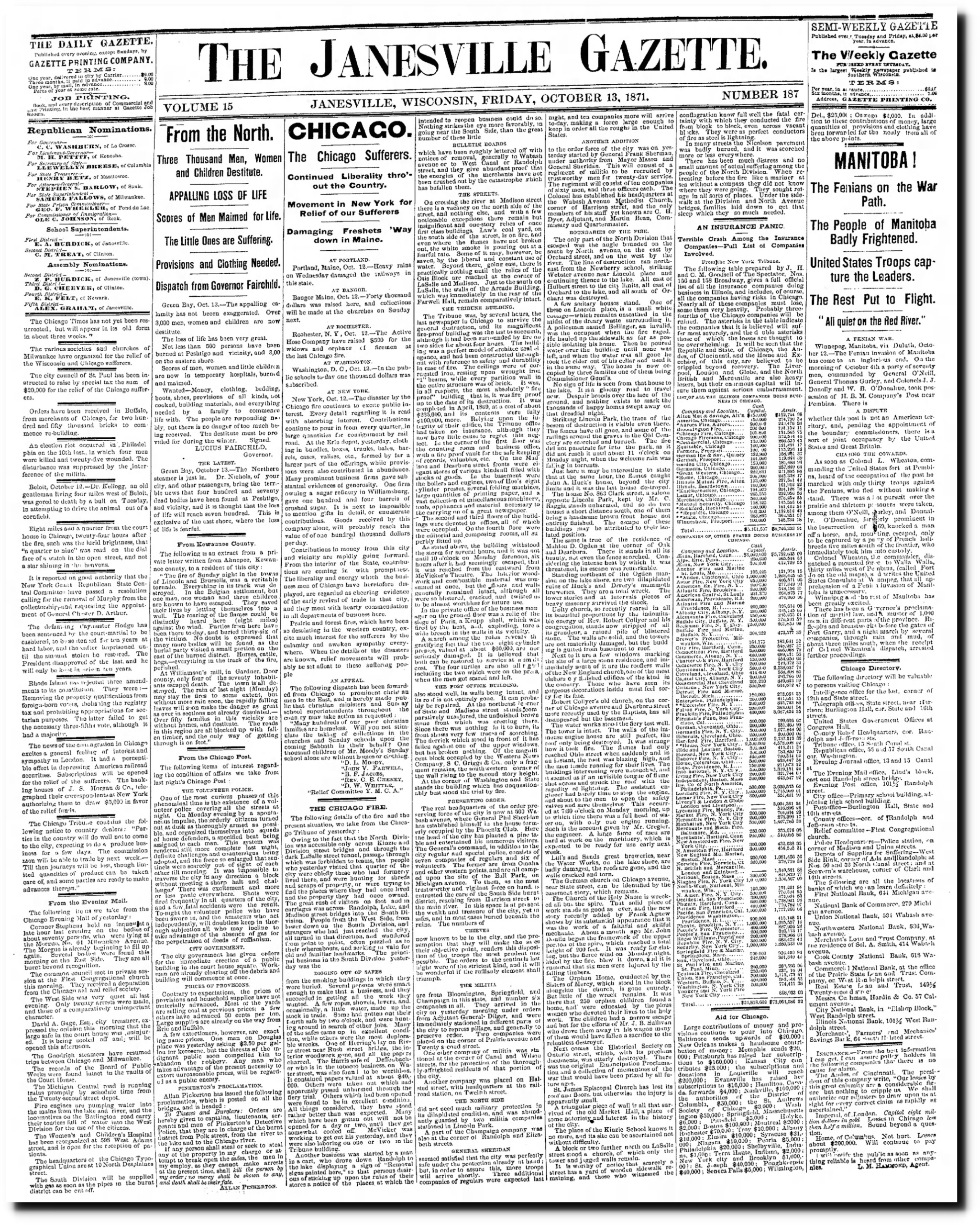

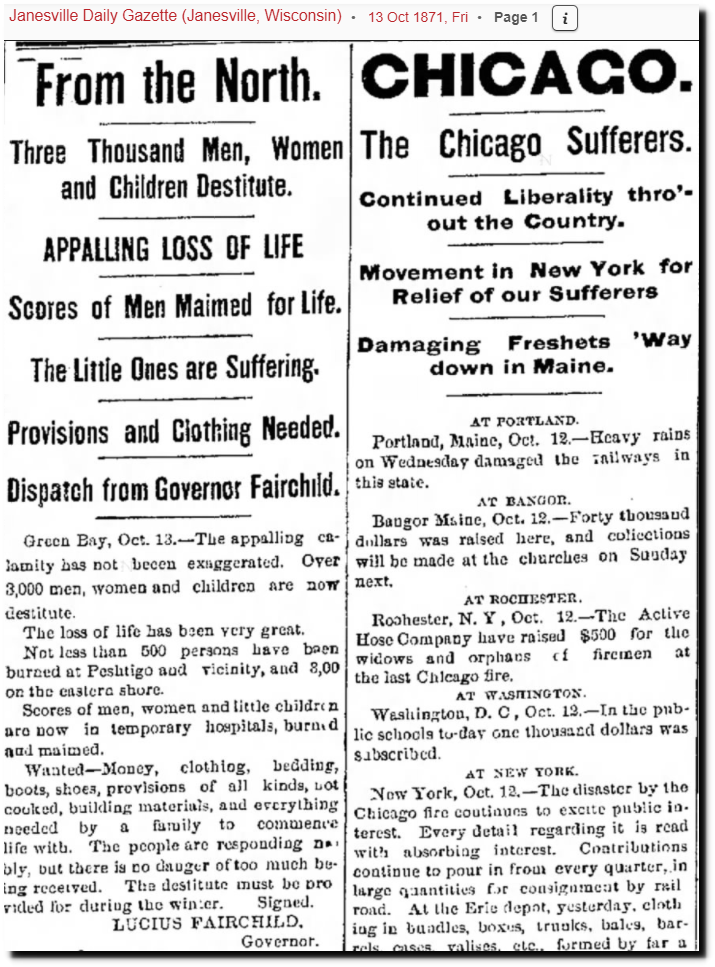

The worst of these fires occurred at Peshtigo, Wisconsin, where more than one thousand people burned to death.

13 Oct 1871, Page 1 – Janesville Daily Gazette at Newspapers.com

13 Oct 1871, 1 – Wisconsin State Journal at Newspapers.com

The current version of history is that the people of Peshtigo had no warning, and this has led to speculation the fires were caused by a meteor or comet.

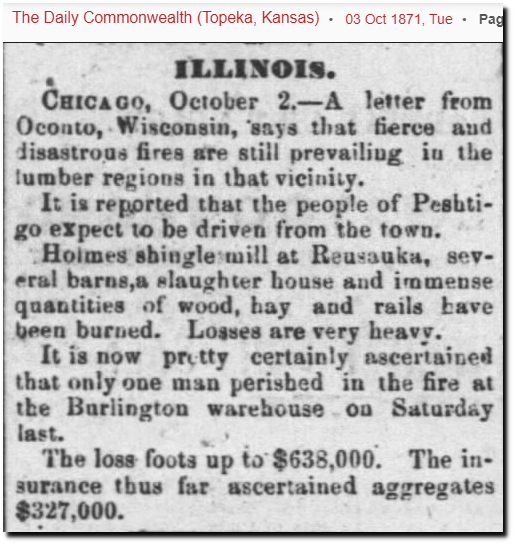

But the reality is – people in Peshtigo knew they were going to be driven from town six days earlier.

03 Oct 1871, 1 – The Daily Commonwealth at Newspapers.com

Here is what really happened.

From 1870 to 1871, the Midwest was engulfed in drought. Peshtigo and the surrounding area, which normally gets a meter or two of snow, got almost none that winter. The spring and summer also brought lighter than normal precipitation. Historical records mark the date of the last soaking rain before the fire as July 8, leaving the slash to bake in the dry air for another three months through summer and early fall.

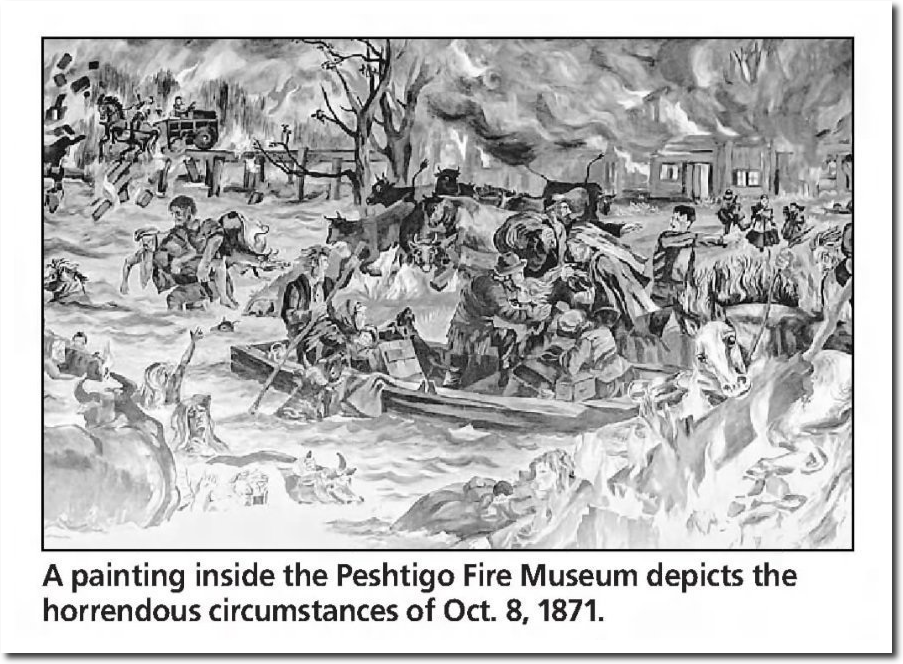

In early October, a cyclonic weather front formed over the Great Plains, creating westerly winds that headed toward Peshtigo. When the storm hit the Northwoods on Oct. 8, a huge temperature difference created strong winds, kicking up coals and fanning the smaller fires, which merged into one enormous fire. A wall of flame nearly 5 kilometers wide and almost a kilometer high roared through the town and quickly spread, according to survivor accounts.

Based on the vitrification of sand, the fire was estimated to have reached more than 1,000 degrees Celsius. It burned so intensely that it created its own weather system, with winds whipping the fire into a tornado-like column of fire and cinders. Authors Gess and Lutz reported that winds rushed through the town at more than 160 kilometers per hour. Escape routes were limited; outrunning the fire was impossible. Many survivors used the same phrase to describe the speed of the flames: “faster than it takes to write these words.”

The combination of conditions that caused the Peshtigo fire and others in the Midwest in October 1871 — normal land-clearing methods, extensive drought conditions and a particularly windy weather front — was not unique or even especially rare. Beginning in spring 2016, wildfires ripped through the Fort McMurray area in Alberta, Canada, burning more than 600,000 hectares. “There was a mild winter and not a lot of meltwater from the mountain snowpack,” said Mike Wotton, a research scientist with the Canadian Forest Service, quoted in a 2016 CBC article. “Then there was an early, hot spring, and everything got very dry. Then on top of that, it got windy,” Wotton said.

“This really shows that once a fire like this is up and running, the only things that are going to stop it [are] if the weather changes or if it runs out of fuel to burn up,” said Mike Flannigan, professor of wildland fire science at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, in the same article. “With a fire like this, it’s burning so hot that air drops [of water by firefighters] are like spitting on a campfire.”